Written by Alba Maria Campos, Spanish volunteer nurse, specialised in family and community health Translate to english by Alba Miquel Photos from X-pro1 © Clara Go - Phone Pic form Alba Mª Campos.

Menstruation is not a passive experience, it is not something that “our body produces for us”; it is something in which we actively play a role in harmony with the cosmic rhythm

A few months ago, a friend told us about a project in one of the most remote places in Nepal: the Far West. He explained a bit about what exactly the project was and the subject took my interest. I had never heard about it before: Chhaupadi.

We said yes immediately. Afterwards, I started reading about the matter, and the more I read, the more interested I became – and more contradictions appeared. Chhaupadi is an Indian tradition which, despite being banned in Nepal since 2005, it is still being practiced in some areas of the country.

Said practice consists of isolating women from their family home for two, three, seven, or even – in some places and castes – up to ten days, during their period. They can’t go into the kitchen, so they are forced to work for longer hours outside their homes. They can’t use the bathroom either, so they have to relieve themselves wherever they are able to. They are not allowed to pray or go to a temple, touch the cows or milk them. They can’t eat fruit, vegetables, meat or dairy products, and handling water is an absolute no-no: they depend on other people every time they need to drink. If they don’t follow these rules, they will be made responsible for any misfortune that may happen to them or their environment. All of this is due to a malediction cast by the God Indra, resulting in women being considered impure and unfavourable for their families every time they menstruate.

I tried to find arguments to support this tradition, to avoid judging it from a Western point of view which would lead me to develop my volunteer work in a “neocolonialist” way – something big NGOs tend to do. When I became aware of the complexity of the issue we were going to tackle, I started to wonder who was I, really, to try and change such deep-rooted customs. Does our Westerness give us the opportunity to live our period the way we would like to? Of course not, but I could not still find the logic in this tradition from a perspective different from patriarchal oppression which oppresses women all around the world. Afterwards, I was surprised that it was the women themselves who made each other go with and through it. Men, apparently, kept aside from it all.

After lots of research, I got hold of an article which somewhat explained some of the pillars supporting this tradition.

From a pranic or energetic point of view, we have five prana, or five types of energy, in our body. One of them is in charge of getting rid of the “impure” – both physically as well as emotionally. I thought that that perspective was very interesting, but it did not justify such a violent attitude. According to such idea, us women were allowed to rest, go away from our entourage and be able to take some days for ourselves, to move our unconscious emotions into the conscious, without judging or analysing them, and thus become in touch with our most inner self. This is a much needed space which is not usually granted in many cultures. During this time, the Shakti (feminine energy) flows throughout our bodies with more intensity, making us more sensitive to the stimuli in our environment, and, likewise, the environment is more affected by it.

Obviously, there is no justification for such mistreatment, defended mainly by older women, and so I decided to focus the program on a self-assessment perspective. They would be the ones to question their way of living menstruation. This would empower them to become free from the superstitions that their families had imprinted in them – which incidentally were not much different from those my grandmother had 50 years ago.

The fear to “recolonise” via volunteering was not the only one crossing my mind. I knew that the trip was not going to be easy: the local buses were mere tin cans with people crammed inside like sardines in a box, and the roads, despite their beauty, were bend after bend, never mind rocks and potholes threatening to roll us over any time. We had been warned, but no obstacle could stop us. Alba and I would start a new adventure.

Another of our fears was the language. Were we going to be able to teach something like this in English? Deep inside, we knew we would get by. But, what would happen with the translations into Nepalese? Who would take care of that?

Two volunteer nurses came with us. In the beginning it was not easy to co-ordinate with each other but, in the end, we ended up quite proud at how we had been able to manage ourselves.

Thanks to the reflections made with the help of the group on health self management – Salut entre Totxs– whom I am very grateful to for their attention, capacity, ponderation, fight and constant critic; as well as to Marta – my lifetime friend whom I had deep conversations about the matter with-, and Julen – an anthropology student who bombarded me with information-, I decided to design the first draft of the program in Barcelona without knowing yet what we would encounter, when or where, until the very last minute.

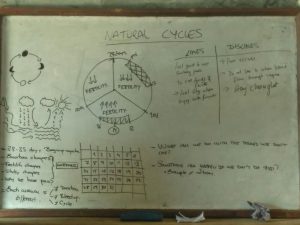

As we were travelling through India, Alba and myself designed the program we would hand over in schools. We included work in the physical and emotional changes during teen years, stressing the emotional ones, with the idea of encouraging consciousness and emotional expression. We also wanted to explain the working of the male and female reproductive systems, highlighting the three orifices and the clitoris. Important too to insist on considering the menstrual cycle as something natural, comparing it to the water and moon cycles, and stressing the more and less fertile days to promote “decision-making capacity” when it came to pregnancies.

We also included a workshop to have the groups explain what was it that girls liked less about their periods, whilst at the same time offering a guided meditation with the boys where they would have to put themselves in the girls’ skins during their period. Afterwards, each group spoke about their feelings before the class. It seemed crucial to us that they would freely talk about and explain the subject in order for them to draw their own conclusions. As a final point, we elaborated on sexual relationships; encompassing love, pleasure for both sexes and reproduction, as well as contraceptive methods. We wondered at the beginning how to tackle this last issue as we did not know how well placed they were to access those methods, and it did surprise us greatly that they themselves raised the subject with questions. At the beginning of the workshop we gave a sheet to each of the attendants so that they could write down all their queries and doubts anonymously so we could reply to all of them.

Finally the moment for us to start our adventure arrived. From Varanasi we went to Lumbini, Danghari and Mangalsen. It took us more than three days to get to Basti. A real overdose of public transport!

We had quite assumed the idea of different rhythms and unexpected events in Nepal, and to be honest everything went quite well. The trip from Mangalsen to Basti was impressive, both for the views as well as for the difficulties. The jeep left us as near as possible. So much that they had to hoist it out with a crane. Then, we walked down a mountain path for three hours accompanied by a group of superwomen, able to carry up to 50 kg. over their heads, whilst their husbands drank, played cards or – many of them – had run away. We were really amazed with the porters, who, in the same way they carry rocks, are burdened with their families and bear the burden of a culture that oppresses them greatly. The first thing we were asked in one of the breaks was if we had a fiancée, if we were married or if we had children. When we said no, they said “that’s very good, discovering the world and enjoying life. We don’t have that opportunity”. Emotions were starting to run high already.

Basti is a village divided into nine districts, and to some it is more than a four hour walk to school, an important fact to bear in mind. Moreover, there are no means of transport other than that, as in the village there are no streets nor is the ground even: it is all mountain field, with hills here and there and rocks that, sometimes, make do as stairs.

The views, wherever we looked, were amazing. There were eagles everywhere. We slept four people in the same bed, we had water only for a few hours a day, electricity depending on sunlight, and we had practically the same food every day. No internet, napkins, toilet paper or hot showers. It was quite funny in fact to shower fully dressed in the village fountain at the same time that we washed our clothes quickly because the water was running out. A real experience worth repeating, even if many would not think the same.

The worst for me was the language barrier. I felt impotent to communicate without a translator. I did not like it either to see only women, and occasionally some young boys and girls, doing all the hard work, besides keeping their homes and taking care of their children. They breast-feed them until rather grown up and spend a lot of time with them. In fact, some even take them to work. The children were free, happy creatures, playing in the streets; dirty and unkempt but with a big smile in their faces, and they always came to take a closer look at us. Where are the screens that so hypnotise children in the West? This is a different world…

The first class we imparted was the photography workshop. We gave them some cameras to take around and make pictures of what they liked less about menstruation to show it to the outside world. A group of women arrived, each from a different female association, which quite moved me. They were very organised, the sort of change generators we needed! In the following session, more than 40 women – many of them breastfeeding their babies on the spot and with their toddlers waddling around – attended the class before going to work. I really enjoyed it! In other lessons we showed them a globe of the Earth and a video explaining the way menstruation is experienced in other parts of the world, and they clapped enthusiastically when we finished. It was also very exciting for us. Moreover, we were careful not to mention the word Chhaupadi at any moment, they themselves were the ones expressing it through their pictures. I made the most of the class on the following day to delve deeper into it with the girls. After they said what they liked the least about menstruation and the boys did the meditation, we drew up conclusions and I asked: do you think something would happen if you didn’t do what you don’t like, if in other parts of the world they can do it in a different way? The boys replied NO unanimously; the girls, after knowing the way of living in other places, started to question what their culture had ingrained in them. The word Chhaupadi was still not being mentioned; we were on the right path! As children very well said, and as everything is always in Nepal: vistare, vistare…

On the 8th of March – Women’s Day -, they made a special cultural program in the village centre with a sign in the background reading: “A Chhaupadi-free village”. You only needed to take a walk around the village to see the huts, where a woman could barely fit, even lying down. And at times there had to be five of them inside. Sometimes, they light fires to warm themselves and there have already been several deaths due to smoke inhalation, not to speak about the sexual violence they suffer, not being able to close the door of the huts from the inside; even if there is a door.

The people of the village were perfectly organised in castes and ages, distributed all around the square. The politicians and the “elite” presiding over the event, the women with their offspring sitting on the floor and the men behind them, in the foreground. Some women were also at the back. Alba and myself, we decided to sit on the floor with them. I was near tears when I saw all that. I would have never imagined that they would organise anything similar. I spent the whole afternoon surrounded by girls who wanted to play the Dholak, very similar to the Madded that a boy was playing in the background, and I felt happy “teaching” them to make noise, with the main objective of attracting the interest of any of them and that the music stopped being just “a men’s thing”. We ended up dancing with them in a big circle to close the event and we went back home exhausted, really excited, and with a great feeling of frustration at not being able to communicate as we would like to.

The last day in Basti was especially intense. A small group of girls arrived to talk about the menstrual cup. One of the girls most interested in the classes and workshops – and who had already tried the menstrual cup, and to whom with entrusted with the task of helping the others if they had any problems with it – arrived. I felt that it would be too complicated having the nurse or the teachers do it themselves: they looked very shy at the subject. It pleased us a lot to share that space with them outside school, they told us a lot of things about their lives and expectations and, to be honest, we were quite amazed. One of them is 16 years old and her parents both work in India, so she lives alone with her younger sister and brother. Her grandmother lives in the house next door and controls that, when they have got her period, they go out from the house and fulfill the tradition. That forced her one time to take contraceptive pills so her period would not happen at the same time as her sister’s, because otherwise none of them could cook or milk the cow. They would not have been able to drink water either, as nobody was there to hand them over a glass. We were quite affected by it and we thought that it was probably just one of many testimonials. Ten days is not enough to really know the reality of a village.

That same day we were faced with two difficult situations that made us go deeper into the reality of these people. The woman who cooked for us had injured her finger with the collar of a cow and hadn’t stopped bleeding since the morning. When we saw it in the afternoon, we saw no option but to stitch it together with the limited equipment we had, and without anaesthetics. Once again, we were amazed by the resilience of these superwomen.

That same night, the son of one of our porters on the first day, had his head injured by a rock thrown at him. He had a very deep gash which would not stop bleeding, and they came to fetch us. We gathered the equipment and again stitched the wound with the last remaining suture thread. This time, we didn’t have gloves either. The house consisted on a single room serving both as kitchen and bedroom, with the only light coming from a fire that filled everything with smoke. There was barely space for the women who were inside. All women. We were in deep shock. What did they usually do in these situations? The nearest hospital was 6 hours away walking across the mountain. I am sure that we were more scared than them, experts in handling adversity and in carrying on with their lives.

The girl that came to talk to us in the house was very clear that she wanted to be a nurse. We felt very proud and encouraged her to do so. Just that same afternoon I had told Alba how happy I was to have followed this career and even more specialise in the family and community area. There is nothing that satisfies me more than to be able to use my skills in any environment and in any place in the world.

Thus has been how, promoting the verbal and artistic expression through photography , by enabling them to picture what they don’t like and giving them basic biopsychosocial information – which is omitted in schools because it is taboo-, we succeeded in having both women and men of all ages question themselves about what they were doing and why. We tried to use different dynamics from those employed by other NGOs that had been in the area, who intended to enforce change using “Western culture invasion” techniques that fall short of being adequate.

Please remember we still need your help to raise funds to continue with our project. You can donate at: https://www.migranodearena.org/en/challenge/13821/rato-baltin-nepal—facing-chhaupadi-with-menstrual-education/